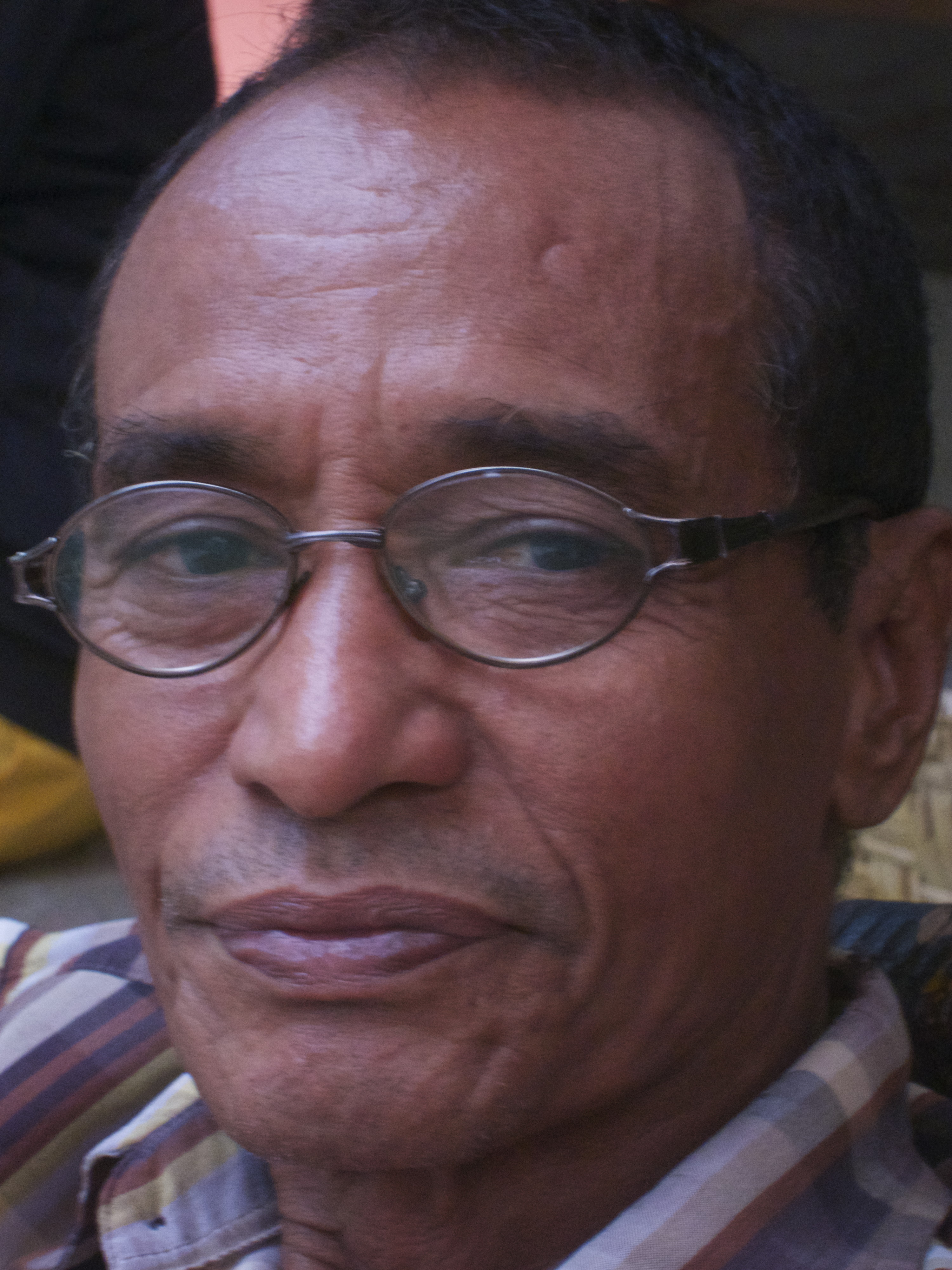

Pedro Lebre, April, 2014

I was first put on to Vila Harmonia by the permaculture guru Lachlan McKenzie, who spend many years in East Timor and drove the creation and publication of a superlative – and practical! – permaculture handbook for East Timor, that incidentally is very applicable for the Top End. In fact, it's probably the best permaculture resource the inland Top End, for places like Katherine, that's around.

I was going to East Timor on a whim, in September 2010, on what turned out to be a very serendipitous trip, from bumping into a long-lost acquaintance on arrival at the airport, to piggy-backing on trips around the country. I'd had no idea about anything in East Timor and Lachie was the only person I knew who did, so I hit him up for info.

Vila Harmonia was, for years, a hub of the resistance, functioning as a guesthouse where foreign activists and journalists could safely get into contact with the Resistance. It's proprietor, Pedro Lebre, is not only a repository of knowledge about the history of East Timor, but, at great personal risk to himself and his family, has been close to many of the events of the last few decades in East Timor's difficult recent history.

He graciously took time out from the book he's writing about his experiences to have a chat about East Timor and his life.

Pedro da Silva Correia Lebre was born in 1952 in Uato-barbau, a Macassae-speaking area to the east of Dili, the closest large town being Baucau, on the coast. The country at the time was still a Portuguese colony, although his direct experience of Portuguese people was very limited; in fact, he didn't see his first Portuguese person until he was eight years old. The fascist dictator, Salazar, who ruled Portugal until his death in 1968, presumably felt holding onto Portugal's colonies bestowed some honour on his country, long after most western countries felt that direct colonial control was acceptable (although we have remained silent about the indirect colonial control we still exercise over much of the world!). Whatever his motives may have been, in practice the country was largely untouched, Portugal's primary contribution being an extractive tax on all adults over 18. They certainly provided very little education, beyond that required to train a small administrative class to serve their needs, and, so I'm told, when they left in the early 1970s, they hadn't sealed any roads outside Dili, nor provided any electricity.

In fact, at least in Pedro's district, the only Portuguese person was the governor. According to Pedro, the Portuguese established a system of village headmen 'liurai' who were very loyal to the governor and were responsible for collecting the head tax, which in 1967, the first year he paid it, was 65 escuardos, which he estimates at about $40.

For people living a traditional tribal or village agricultural life in a cashless economy, this was a significant burden, requiring them to sell livestock or submit to poorly paid labour, often in harsh conditions. Pedro says that for many people, liberation from the Portuguese meant liberation from this burdensome tax.

Pedro spent four years at the local Portuguese-provided school, but after that wasn't able to continue his education by staying in his village, as his parents didn't have the means to pay for the church-run school that provided further education. He decided to leave his homeland and finish primary school in Baucau, after which he returned home. He was still anxious to continue his education so after a period returned to Baucau and found work in the Pousada in Baucau, a grand government hotel that is still well-known in East Timor. He worked there for three years and it was there that he got to know an Australian, Anthony Ferris who, through the Kensington (Melbourne) branch of Rotary, supported him to study at a technical school in Dili. He didn't finish this course, however, as, being one of the few East Timorese with both good English and some scientific knowledge, he was in high demand and went to work for BHP.

His association with Australians and other foreigners who openly criticised the Portuguese colonialists put him in a difficult position. The climate amongst the Portuguese government was increasingly sensitive to sedition in its remaining colonies (at this time Mozambique was fighting a war of independence against the Portuguese) and, although he wasn't involved in any seditious activities, his association with westerners put him at risk of suspicion by the Portuguese, so, for the sake of his safety, and to continue his education, he left for Australia. Two weeks later, when in Darwin, he got the news that the Portuguese had granted independence to East Timor!

The subsequent short independence and following occupation by, and war with, Indonesia is a big topic and we didn't cover it, except to briefly talk about East Timor. Although there appears to be increasing problems with corruption and a rich elite (both those things being connected!), most people in East Timor are very proud of the independence they achieved and optimistic about the future. Although he has many links to the resistance leaders, many of whom occupy top positions in the government and bureaucracy, Pedro is not a politician and isn't interested in participating in politicial life. 'I'm not a politician – I'm a nationalist. I love my country'

Pedro Lebre at home. His first grandson, Libertad, born just after independence, is sitting behind him.

A few words from Pedo in English...

... and in Tetun

A few photos of Vila Harmonia taken over a few visits

View from the bedroom porch (April, 2014)

Breakfast (March, 2012)

Breakfast (March, 2012)